The publication of a new study reveals that there has been very strong atmospheric methane growth in the four years 2014‐2017. This has huge implications for the goals of the Paris Climate agreement.

The Potency of Methane

Methane, CH4, is the forgotten sibling of CO2 , perhaps because it only accounts for 20% of the radiative forcing. Alas, it now rears its head and yells at us. It is also highly potent. When compared to CO2, it traps 28 times more heat.

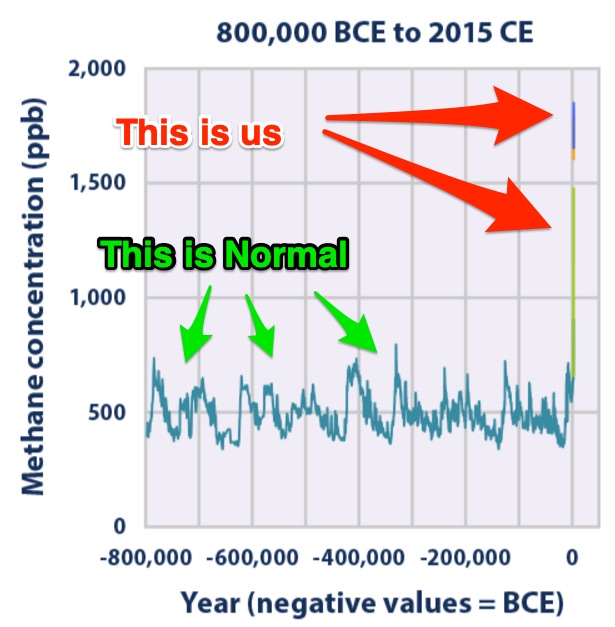

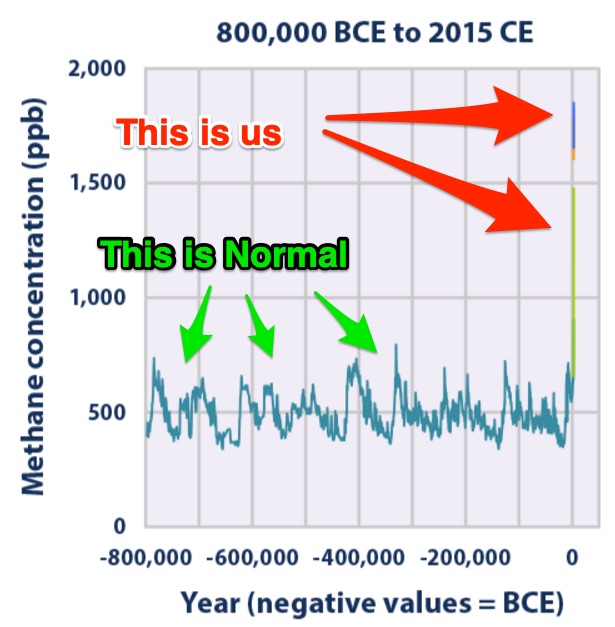

Historically levels have fluctuated in the range 300-400 parts per billion (ppb) during glacial periods and 600-700 pub during warmer interglacial periods, then human activities kicked in. It has been observed to have risen to over 1886 ppb. You can find a NOAA dataset with precise measurements here.

The new Study

Published within the AGU Global Biogeochemical Cycles on 5th February and titled “Very strong atmospheric methane growth in the four years 2014‐2017: Implications for the Paris Agreement”, it lays out the details of what has been happening …

The rise in atmospheric methane (CH4), which began in 2007, accelerated in the past four years. The growth has been worldwide, especially in the tropics and northern mid‐latitudes. With the rise has come a shift in the carbon isotope ratio of the methane. The causes of the rise are not fully understood, and may include increased emissions and perhaps a decline in the destruction of methane in the air. Methane’s increase since 2007 was not expected in future greenhouse gas scenarios compliant with the targets of the Paris Agreement, and if the increase continues at the same rates it may become very difficult to meet the Paris goals. There is now urgent need to reduce methane emissions, especially from the fossil fuel industry.

What exactly has been happening?

In the 1990s, the atmospheric methane burden trended towards quilibrium, which it reached by the end of the 20th century, with little or no growth in its atmospheric burden in the early years of this century. In 1984, the first year with detailed records, the global annual average atmospheric mole fraction of methane in the remote marine boundary layer was 1645 ppb. In 2006, just before the recent growth phase began, it was about 1775 ppb. This then grew rapidly to an annual global mean of 1850 ppb in 2017, a total rise of about 75 ppb in the 2007-2017 period. That increase is continuing.

The annual increase in atmospheric CH4 in a given year is the increase in its abundance (mole fraction) from January 1 in that year to January 1 of the next year, after the seasonal cycle has been removed (as shown by the black lines in the figure above). It represents the sum of all CH4 added to, and removed from, the atmosphere during the year by human activities and natural processes.

How much has it been increasing by each year?

The table below spells it out. The middle column is the increase (or decrease) expressed in ppt/yr,

Why is it increasing, where is it all coming from?

We don’t fully understand what is happening, but there are three ideas discussed within the new study …

- An increase in the proportion of global emissions from microbial sources (wetlands) may have driven the increase

- Or … a strong rise in methane emissions from the use of natural gas and oil has taken place.

- Or … the oxidative capacity –the cleansing power -of the atmosphere has declined, and hence the destruction of methane has slowed. Even if total emissions have changed little or (less likely) even decreased, the observed increased can be explained by this.

It need not be a binary choice. Some or all of the above may together explain it.

The uptick is a surprise and a shock

Although methane’s apparent equilibration in the early years of this century was perhaps only a temporary pause in the human-induced increase in atmospheric methane, the renewed strong methane growth that began in 2007 was so unexpected that it was not considered in pathway models preparatory to the Paris Agreement.

The current growth has now lasted over a decade. If growth continues at similar rates through subsequent decades, evidence presented within the new study demonstrates that the extra climate warming impact of this methane can significantly negate or even reverse progress in climate mitigation from reducing CO2 emissions. This will challenge efforts to meet the target of the 2015 UN Paris Agreement on Climate Change, to limit climate warming to 2°C.

Regardless of why this is happening, the observational fact is huge news, and yet will probably also not attract the attention needed.

Author Comments

…“What we are now witnessing is extremely worrying,” said one of the paper’s lead authors, Professor Euan Nisbet of Royal Holloway, University of London. “It is particularly alarming because we are still not sure why atmospheric methane levels are rising across the planet.”…

…“We have only just started analysing our data but have already found evidence that a great plume of methane now rises above the wetland swamps of Lake Bangweul in Zambia,” added Nisbet….

…“It was assumed, at the time of the Paris, agreement, that reducing the amount of methane in the atmosphere would be relatively easy and that the hard work would involve cutting CO2emissions.

“However, that does not look so simple any more. We don’t know exactly what is happening.

“Perhaps emissions are growing or perhaps the problem is due to the fact that our atmosphere is losing its ability to break down methane.

“Either way we are facing a very worrying problem. That is why it is so important that we unravel what is going on – as soon as possible.”

Further Reading

Nature (6th Feb 2019) – Tropical Africa could be a key to solving methane mystery

Armed with an aeroplane loaded with sampling equipment, UK scientists have taken the most detailed measurements yet of the methane in the skies over tropical Africa. The data should help researchers to understand a mysterious spike in atmospheric concentrations of the powerful greenhouse gas, which began in 2007.

The flights started in Uganda in January and ended this week in Zambia. Researchers sampled methane emissions emanating from papyrus swamps, burning farm fields and flatulent livestock. Early results confirm that Africa is playing a major, yet poorly documented, role in the global methane cycle, with enormous consequences for the global climate.

The above field trip is being led by Euan Nisbet. He is also the lead author of the newly published study.